“Knowing the audience” on digital platforms

How dashboards steer cultural production

Jan Teurlings

“I think that as soon as you’ve recorded a song it doesn’t belong to you anymore. It just goes out and everyone can sing it, everyone can do it if they want. They can change it. You know what I mean? It’s not yours. It’s yours when you are playing it in your bedroom or something it’s still private, but when you’ve let it out you’ve got to get on with something else”

This quote from a 1974 interview with Mick Jagger is ostensibly about the ownership of immaterial-yet-public cultural goods like songs, but underlying it is a problem that all cultural producers inevitably confront, namely that it is impossible to know and control where the fruits of their creative labour end up. This is especially so for cultural goods that are technologically mediated (as opposed to those cultural forms that rely on physical proximity). The fact that the former are technologically mediated undoubtedly increases their reach but in the very same operation makes this reach “unknowable”. This was particularly glaring during the broadcast era, where signals were thrust into the ether without the sender receiving any kind of information on where their messages would land. But also in non-broadcast arrangements the impossibility of knowing the audience lingers: the writer of a novel, the author of a tweet, and indeed, the songwriter, do not know, nor fully control, where their creations end up.

As the internet became the dominant distribution medium for all kinds of content, the promise was that this “unknowability of the audience” would come to an end. This became particularly prominent with “the rise of the platform as the dominant infrastructural and economic model of the social web”, (Helmond 2015: 1), or in short, the internet’s platformization. A platform creates a semi-closed digital environment that is able to track all interactions within its ambit. This means that the Netflixes, Disney+’es and YouTubes of this world not only tightly control the content they serve, but also to whom and under what conditions (think of user log-ins and parental filters). In short, a platform, in its very nature, promises to make the entire communication chain transparent (and hence controllable).

For content producers, this makes platforms an appealing environment to distribute their creations, since they offer the possibility to know their audiences. Most platforms therefore offer contributors insight into the reach of their creations, in the form of dashboards that contain audience metrics. Even though these dashboards are based on data it is important to stress that they format the latter (Tkacz 2022), meaning that they inevitably offer a selection of all available data and that they entail a translation from data formats to another. This implies that the knowledge about the audience given to content creators is “interested”, in the sense that the knowledge is not random nor complete, and in its biases it is possible to detect a certain managerial logic.

A closer look into these dashboards, then, tells us a lot about the kinds of knowledge and insights these platforms send to the contributors. This, in turn, allows us to analyse how platforms steer creative production, given the interestedness of the dashboard. Taking YouTube’s creator dashboard as a case study, we can make the following observations.

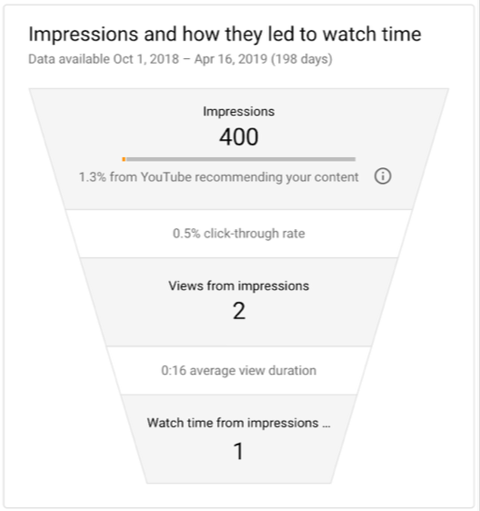

Picture 1

1. Behaviourist knowledge on the audience is privileged, rather than its social-demographic composition. To be sure, creators are offered a limited number of socio-demographic variables of the audience, like age, gender, geographical location, but this comes nowhere near the socio-demographic sophistication Nielsen rating offer to content producers. Instead, there is an at times bewildering multiplication of behaviourist metrics: new and returning users, unique viewers, subscribers, retention rate, adjacent audiences, other video’s your audience watched, etc… All are data that describe the audience’s behaviour rather than who they are – their identity.

2. This behaviourist knowledge nudges the creators towards adapting or experimenting with the content they produce. Take for instance the “other videos your audience watched” metric. In the help file, this is described as “[t]his report shows you what other videos your viewers watched outside your channel over the past 7 days. You can use it to find topics for new videos and titles. You can also use the info for thumbnail ideas […]”. Here the difference between “knowing your audience” and creative advice becomes razor thin.

3. In terms of interests, the metrics are clearly aimed at growing the audience of a channel. This can be seen in the prominent place given to the number of subscribers on the dashboard’s landing page, but also in the impressions and click-through rate overview, which shows how many users were confronted with a thumbnail, clicked through, and then actually watched the video. This metric offers insights into which thumbnails work better than others in attracting audiences, and stimulates creators increasing their reach audience.

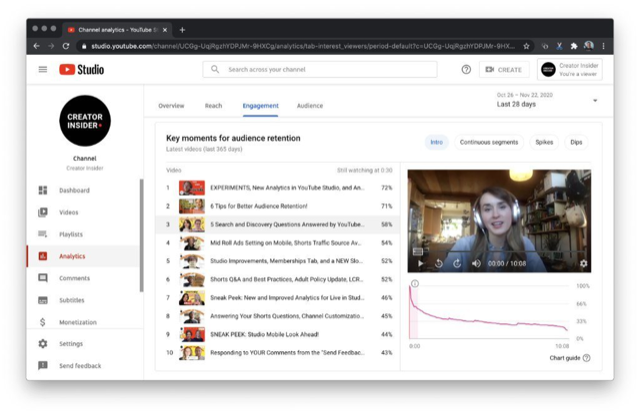

Picture 2

4. The platform clearly privileges increasing the watch time, of single video’s but also of a channel. That is why a channel’s overall watch time is featured on the dashboard’s landing page. Also metrics like the audience retention rate, offering a timeline that shows at which point in time viewers stopped watching a clip, clearly stimulates creators to maximizing the viewing time, by tinkering and experimenting with the video.

Picture 3

To conclude then: platforms offer cultural creators insights into their audiences, but this knowledge is heavily skewed towards observable behaviour, rather than insights on how users experience or appreciate their products. As Baym et al. have argued, data are not an unmediated inroad to the actual audience; they also require interpretation, and bridging the gap between the audience and its representation-in-data remains an elusive endeavour. Yet despite the impossibility of fully knowing the audience, the metrics do steer cultural production in the platform age.

Bibliographie

Baym, Nancy, Rachel Bergmann, Raj Bhargava, Fernando Diaz, Tarleton Gillespie, David Hesmondhalgh, and others. (2021). Making Sense of Metrics in the Music Industries. International Journal of Communication, 15, 3418-41

Helmond, Anne. (2015). The Platformization of the Web: Making Web Data Platform Ready. Social Media + Society, 1.2: 1-11. Tkacz, Nathaniel. (2022). Being With Data: The Dashboarding of Everyday Life, Cambridge, Polity